The Splinter of My Mind

On the Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon, Olafur Eliasson's OPEN Exhibit, and LinkedIn Diversity Questions

In his massive, site-specific installation exhibit nebulously titled “OPEN” at the Geffen Contemporary at MoCA, the Icelandic-Danish, Berlin-based artist Olafur Eliasson claims he is “not looking for a single, clear answer.” In behemoth contraptions made from a cornucopia of industrial materials, Eliasson poses questions about humanity’s self-perception, gathering us all inside the ever-expanding systems which govern our lives. What bravery to present anything that doesn’t come with preconceived answers and hope for its own mission. It is all well and good to intentionally center a piece of art on questions alone, but to be purposefully uninterested in answers seems astonishing to me. How does one sit comfortably in a question mark?

Eliasson’s gargantuan work, both in terms of scope and mission, plays with the viewer’s literal perception of spatial dynamics. In form this translates to pieces which challenge the eye in direct and indirect ways, as with “The listening dimension,” in which large, semicircular tubes mounted within wall-sized mirrors give the initial impression of hovering circles in infinite space. Eliasson’s work is persistently cheeky, using incomplete materials and finite edges to elicit considerations of endlessness. He employs materially defined terms to suggest undefined existences.

Without a careful eye, the exhibit can risk dallying with the more nefariously broad aspects of capitalist art. I worried that Eliasson’s challenging questions, posted on multiple walls like the space’s reading room, if viewers are “open” to a series of questions, might seem like they could be appropriate on mass-produced wall art found in stores like Target. “AM I OPEN,” the questions all begin, “to vulnerability?” or else “to wonder?” or “to engaging fully with my senses?” Outside of the installation’s context, these questions can induce an eye-roll.

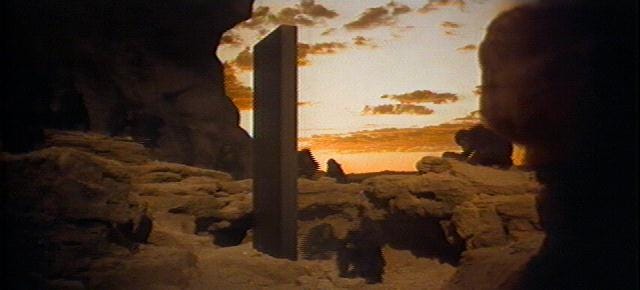

But within the context of the artist’s most wildly inventive constructions, the questions implicate the viewer in the engagement of, and activation in, the piece in question. In “Pluriverse assembly,” which uses a room-length LED projection screen in front of a series of electrical ballasts, control units and motors which constantly, and imperceptibly, shift the positioning of a panoply of mechanical pieces, the museum-goer is faced with an infinitude of possibilities of light. Shapes are being constantly created anew in a shadow play which suggests whole universes, or the meeting with God implied through Stanley Kubrick’s recurring black slab in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Other pieces play with infinity and plurality through more simple plays with light and mirroring. In “Observatory for seeing the atmosphere’s futures,” viewers are invited to stand underneath a towering structure which pierces the Geffen roof. Staring up through the escalating reflections at the small window of natural light, it becomes impossible not to see the self, an infinite version of the self, ascending into the daytime sky.

——

I remember when I first started watching soccer, around the time of the World Cup in 2014, I started to see European jerseys everywhere I went. It wasn’t that there was some global change in which suddenly everyone, like me, had discovered the sport at the same time, but that once you recognize something as part of your own life you begin to actually see it more regularly. I had no cause to notice a Barcelona kit or a Liverpool scarf pre-2014 because I didn’t even know the clubs which produced the merchandise. This is a common occurrence known as the Frequency Illusion, a cognitive bias which creates the false perception that a thing exists more often than it actually does after one becomes aware of the thing’s existence. The bias is also known as the Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon thanks to Terry Mullen, who wrote to the St. Paul Pioneer Press in 1994 about his inability to unsee the phrase “Baader-Meinhof” after learning about the 1970-1998 German group of the same name.

Recently, I’ve had another Baader-Meinhof-esque cognitive bias I’ve had a harder time dismissing. With a sudden and increasing alacrity, I have been considering what it means to be male, and have seen gender in all things. My maleness, something I have not previously considered as a matter for debate, has become more porous. I have gone from tacit acceptance of the label I was given as a child to curious, if frightened, appraiser. It feels a bit like removing a piece of art from the corner of a closet you forgot you put away years ago, and though it seems similar to what it was when you got it, your perception of life, of art, of representation, has morphed considerably - and so has your understanding of the piece itself. Or perhaps it’s a classic novel I read in high school; my gender has become like an old copy of Willa Cather’s My Antonia, or John Williams’s Stoner, stories I assumed whose meaning and purpose was already canonized and which could not be re-evaluated. As a cinephile, I understand how the classics can be re-evaluated over time (indeed that ability to change over time is what often makes the film so special), but I have nonetheless been surprised at this revelation in how I define myself.

This sudden reconsideration kicked into high gear, a bit embarrassingly, through LinkedIn; I have been seemingly stuck in a two year period of endless job hunting. Though I technically have three jobs, none of them provide neither financial solvency nor a profound sense of purpose, and since capitalism can make us feel like no amount of sheer effort is ever enough, I often feel no more productive than my cat-like and aging dog. Most job applications now have a diversity section of voluntary disclosure, and it has become a sticking point of self-evaluation. For one thing, I am constantly debating if I should mention that I have a disability as someone who deals with the fervently seismic waves of Major Depressive Disorder. I wrestle with the label, but being that it is legally recognized as such and that I have survived two suicide attempts, should I mark it?

More pressingly lately has been the previously simple drop-down menu to disclose my gender. Some applications list the options as “male,” “female” or “other” (how diminutive, that “other” which is inherently othering). Some applications have a third option that just says “prefer not to disclose,” which too feels strange and challenging, as if all gender-queer people would choose hiding in lieu of being misgendered as cis. Both in terms of gender and disability, I wonder if my selection matters to anyone but myself - which, depending on the day, can make me either more or less eager to identify the way I want to identify.

I don’t know exactly when, but at some point selecting male felt wrong, or at least not entirely correct. Choosing it as my option felt like being cleaved. Choosing that preference “not to disclose” felt wrong too; I do want to disclose. It’s just that I am not sure yet how. It is a persistently thorny torn in the side of queerness that we seek to exist as living challenges to structural binaries, yet frustratingly must self-label in a desire for self-actualization. In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson calls this “irresolution.” “On the one hand,” she wonders, “the Aristotelian, perhaps evolutionary need to put everything into categories— predator, twilight, edible— on the other, the need to pay homage to the transitive, the flight, the great soup of being in which we actually live.”

Noticing my own irresolution with gender has been singularly distressing, because, as in all things, I find it hard to move forward without having a certain completeness of knowledge. This aversion of mess, coupled with a genuine pleasure in research, has probably prevented me from moving forward with any number of artistic ideas. And now, with identity, I have wondered how I can declare that I am non-binary if I am still unaware how to define what that means. But, if a globally respected artist like Olafur Eliasson can mount a major exhibition with an acute disinterest in clarity - and in its place a curiosity for un-knowledge - why can’t I indulge in an identity that is inherently in flux?

I am trying to understand that the “irresolution” is also liberatory for almost the same reasons. Convenient though it is, I know that my own journey to a new kind of gender identity did not begin or end with LinkedIn job applications. More accurately I might point out that, over the last couple years, as I’ve built in fits and starts a solo show structurally based on the surrealist writing of Italo Calvino, I have inadvertently forced myself to confront some base stories which I am only beginning to dismantle. Some of those stories are political (the tenuous line from Holocaust survivalism to Palestinian subjugation) and some are about the nature of art-making itself (the poisonous notion that one cannot begin to create without knowing the end). But because the show is predicated on several lines between several realities, I have unconsciously asked myself to further question one of the foundations of my own existence. It has become clear to me lately that the interconnectedness of how I write, perform, create, think about politics, have sex; how I talk, how I listen, and how I advocate - all of these modus operandi exist within a challenging wholeness of being. A wholeness that I no longer think can be held within the singular definitions of binary gender. The very film which I have long considered a personal favorite, Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963), exists on an endless plenitude of possibilities. My queerness has always, subconsciously, reached into every realm of my existence.

While thinking in this new way feels mostly intellectual and as a matter of the heart, I have noticed that considering myself as neither here nor there has created an exhilarating brain tingling and physiological connection I could not have previously predicted, much more powerful than when I inadvertently came out as bisexual via a fluff piece in Elle Magazine (long story). It feels not unlike how I sometimes feel after leaving a session with my EMDR-practicing therapist, or like the handful of times I’ve taken mushrooms. It is like a wedge has been slightly lodged between the hemispheres of my body, awakening long dormant nervous systems and buried memories (one of which has curiously been the time when a stranger at a party in Bushwick drunkenly told me I had “lesbian energy”).

It also feels like a “splinter” in my mind, as Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne) relates to Neo (Keanu Reeves) in The Matrix (1999). Directed by trans siblings The Wachowskis, the film has morphed over time into a key trans text, dramatizing as it does what so many non-binary and trans folk feel about public versus private personae, how capitalism exacerbates heteronormative gender roles and empty moneyed pursuits, and, most importantly, the distinct feeling that something is not quite right.

Though I’ve seen the film perhaps more often than any other in my life, I rewatched it on the encouragement of a trans friend who insisted upon it after I told her how I’m feeling. And, because I am more or less indulging in my own Baader-Meinhof bias, wherein so many things I previously assumed to be non-gendered have revealed themselves to be supremely so, I cannot walk away from the film, or the Eliasson installations, without learning something more about me. “You've felt it your entire life,” Morpheus tells Neo, “that there's something wrong with the world. You don't know what it is, but it's there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad." Being a biblical allegory of a film, it is perhaps unsurprising the quote is something of an adaptation of Matthew 7:3-5:

"Why do you see the speck in your neighbor's eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye? Or how can you say to your neighbor, 'Let me take the speck out of your eye' while the log is in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbor's eye"

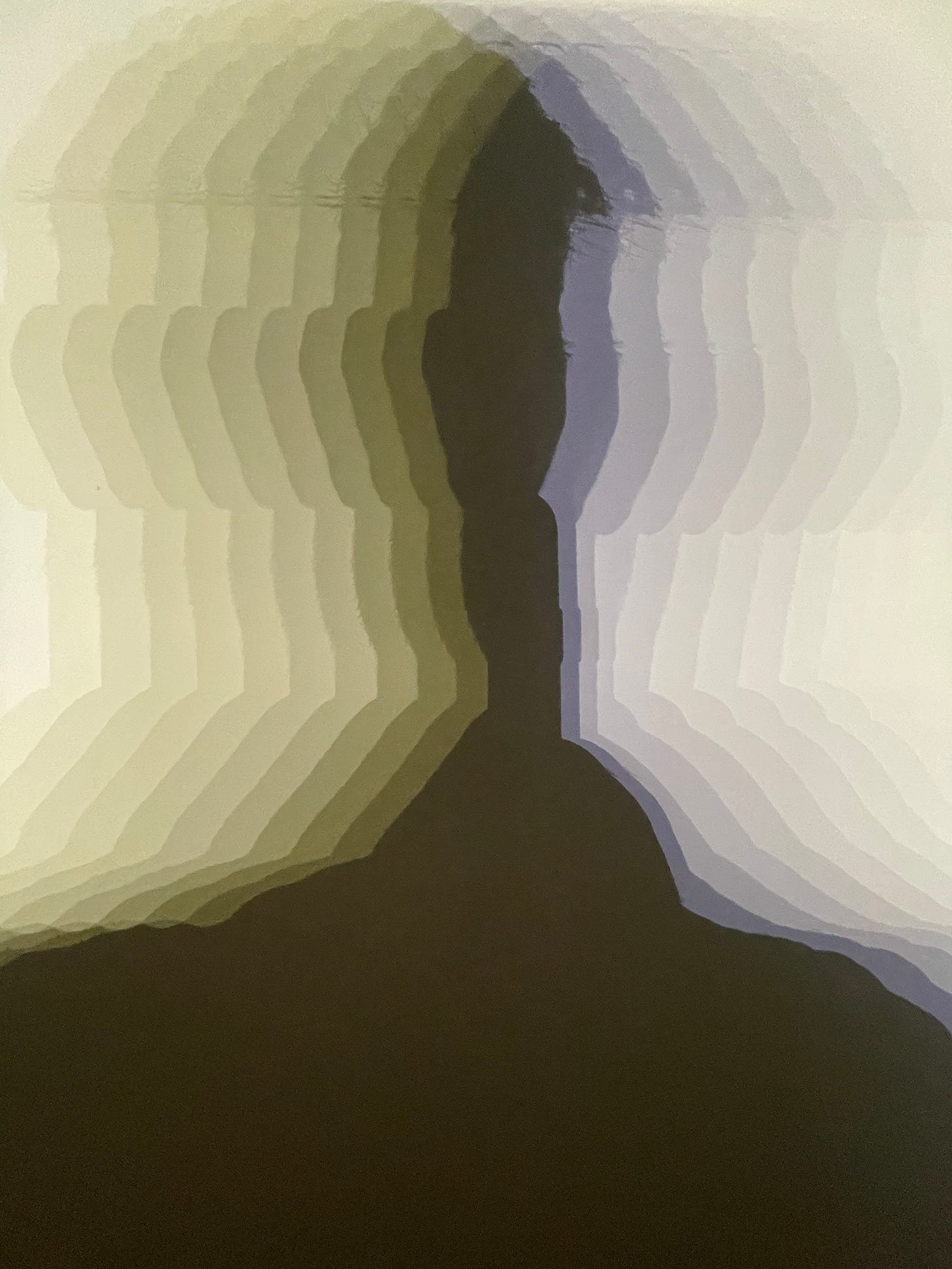

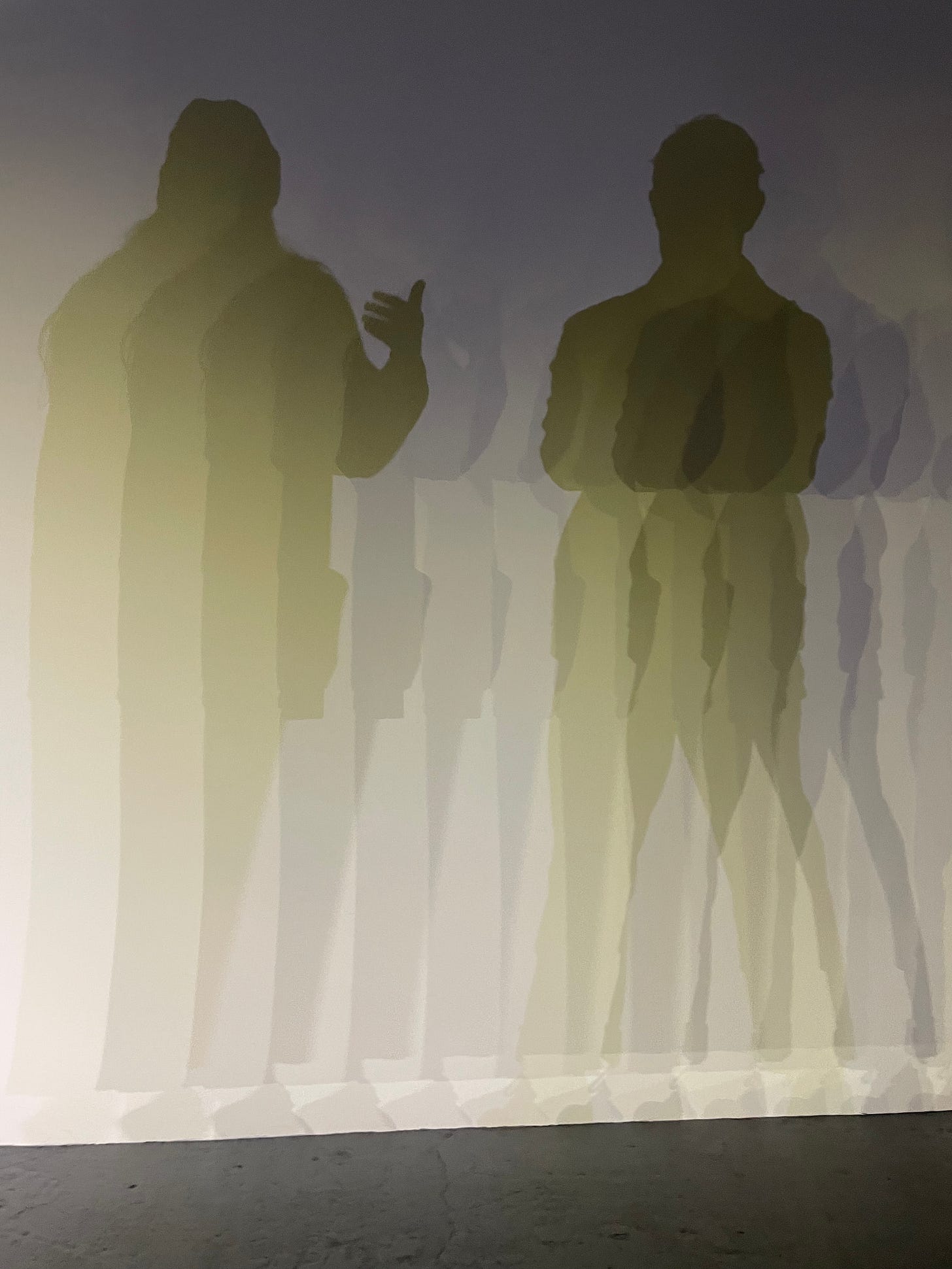

But what if I don’t want to remove the log? My friend Jon reminded me of Theodor Adorno’s riff on Matthew, that the “splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass.” Indeed the magnifying glass has led to an unraveling of my guts, and I am becoming interested in the violence. Baader-Meinhof in my mind, I entered into Eliasson’s piece “Your sunset shadow” almost seeking out representations of my multitudinousness. His most audience-reliant piece, the shadow play is dependent on people walking across a set of eleven white and yellow color filters on LED projectors which create silhouettes on the far wall. No matter where one stands, or how one approaches the wall, there is no way to create a uniform shadow of the self. One is always split into several copies; though the intensity of the shadows and the scales can shift, there is a permanence of silhouetted echoes. Walking through the projections with one of my closest friends, moments after telling them about my fractured sense of identity, I felt as if I had stumbled onto an otherworldly gift.

Neo gets his answers in The Matrix. Unlike Eliasson, the search for infinity yields definition. Though it surprises me to say it, I believe I am probably growing more comfortable with the not-knowing than the knowing. I am living in the in between, striving for solace in uncertainty.

Incredible, beautifully captured and written xoxoxo

One of the best and most evocative pieces I've ever read. Phenomenal.